Originally published in Sports Cars Illustrated in December 1958.

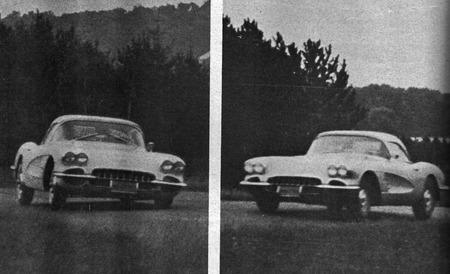

Alone amongst sports cars, Corvette sticks to the Detroit habit of annual changes. Though far from all-new, the ’59 models incorporate some interesting innovations; so much so that we opted for a comparison test of old and new at GM’s Milford, Michigan Proving Grounds. Though but two Corvettes were sampled, we came away with a headful of contrasting thoughts, for they were as different as night from day. The white one sported all the ’59 body and interior changes on a strictly boulevard ’58 chassis—normal suspension, three-speed box (we drove off in reverse at first) and the single-quad equipped 283 cu in V-8 engine. It was, in fact, a mobile display car for itinerant journalists. The other machine was a choice item indeed. Though camouflaged by the older body—washboard hood panel and chrome trim strips on the trunk—it had all the chassis mods for ’59, which included a four-speed box, Positraction rear and a “works-built” full-house power plant. Just our meat, and no wonder; it’s Zora Arkus-Duntov’s own company car, a natural test bed for new ideas.

One of them fills a long-felt need. To better control the movement of the relatively heavy rigid rear axle, radius rods have been fitted to it above each rear spring. Running forward to the boxed frame, they are merely shortened versions of the Panhard rod which will be standard on ’59 Chevy passenger cars. Thus relieved of a burdensome additional duty, the rear shock absorbers are now mounted straight up and down and are recalibrated. Result: a slightly softer ride and noticeably less rear-end steering on irregular surfaces.

Two changes permit still faster shifts than ever on the excellent all-synchro four-speed transmission. Clutch pedal travel, normally 6.4 in, may be reduced to 4.5 by rearranging part of the clutch linkage. And to avoid getting lost in the reverse gate when snapping off a downshift from third to second, the springloaded detent has given way to what the GM people call a “positive-action reverse inhibitor for 4-speed transmission.” Translated into everyday mechanical lingo, this means a T-handled positive lock mounted on the shift lever which you pull up with two fingers as you shift the lever over with the palm of your hand into the reverse gate.

The above changes, all very nice ones, are all standard items. The biggest news and the best is going to start out as an option. This is in the brake department where Moraine sintered metallic lining pads will now be available on any Corvette, with or without the heavy duty suspension, and, we suspect, eventually on any Chevrolet at all. Like the Bendix cerametallic linings, these attack the brake fade problem from the fade resistance angle rather than from the heat dissipation point of view, as Buick does with their now-bonded aluminum cast iron drums. But Moraine engineers have achieved, after more than a year of testing by Mauri Rose, what could not be done with the cerametallic pads; namely, keeping the drums from wearing out before the pads, and avoiding brake-grab when the stoppers are still cold.

Another problem with the “Not for road use” Bendix binders was that once the drums were scored, which was generally pretty darn soon, the braking was apt to be erratic. It was just enough to make the Corvettes twitch a bit at the ends of the long straights. Mr. Duntov says that despite this roughness, these cerametallic set-ups could last through two Sebrings in a row. Indeed, while we were in his office, he received a call from an owner-driver on the Pacific Coast who has just finished his second consecutive season on the same set of drums and shoes.

Leave a Reply