TESTED

Steering gets plenty quick at 140 mph. And the suspension, which felt like flint on Sunset Strip, is supple, almost loose. In this high-velocity never-neverland all your senses need reorientation: A road that looks mirror flat pitches you violently up and down; the air makes tortured noises you hear right through the glass as it scrapes over the top of the windshield; an unseen force slowly twists and tortures the outside mirror until it surrenders and ends up pointing skyward.

Keeping the car, and yourself, on the straight and narrow is so much a hairtrigger operation that it takes your logical conscience about three miles to break through your concentration — you haven’t got time to carry on a mental debate about the morality of what you are doing. But when that logical, practical conscience does break through, it is not amused. Bad enough to spend a day driving to Nevada, but to tempt the worst kind of destruction by running a 454 Corvette right up to the redline in top gear and hold it there is damn near unAmerican. There is no defense. No rational excuse for driving along at double the posted speed limits in any other state.

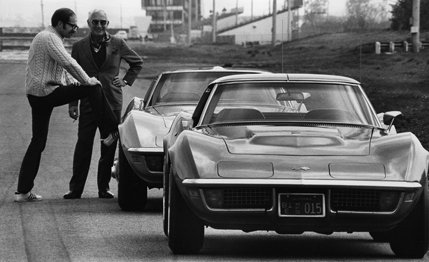

Rationale be damned; plead “temporary enthusiasm” and get it over with. And get back to the beauty of it. Because that’s what happens. It happens to anybody who spends a few days with Zora Arkus-Duntov testing Corvettes of every engine description that Chevrolet makes in 1971: running them on the drag strip, around the skid pad and through a makeshift road course. And all the time talking to Duntov about it, about what he did to the suspension and the tires and the aerodynamics so that the Corvette is the only car built in America that can run 140 mph no sweat and the driver doesn’t have to worry about becoming history.

|

|

Later, when the driving is finished for the day, there is dinner and maybe a few drinks and more talk — talk about what it was like back when the Delahayes and the Talbots were trying to knock off the Mercedes and Auto Union juggernauts on the Grand Prix circuit; about how Duntov got the idea for the “Ardun” cylinderhead conversion while driving his flat-head Ford wide open across France one day before the war; about what it was like to work with Sydney Allard and drive an Allard at Le Mans and lose, then to switch to Porsche and win the class the next two years in a row.

But whether it is between courses at dinner or while the condensation was running down a Martini glass, Corvettes are never far below the surface. Little by little glimpses of automotive history would come out — things that put today, and the 1971 Corvette, into perspective: That he had worked with a brilliant engineer named John Dolza on the Rochester fuel-injection and the system is fundamentally sound today except that cubic inches are a cheaper way to horsepower; that the “Duntov” cam was an emergency horsepower device he developed when Chevrolet wanted to crack 150 mph on Daytona Beach in 1956; the contempt Duntov feels for the body shape of the 1963-1967 Sting Ray because it had “just enough lift to be a bad airplane.”

|

|

There are discussions of current technology and sketches on napkins; penciled-in arrows show that air doesn’t enter the radiator of the current Corvette through the grille — it is blocked off by the license plates and the head light shields — instead air is shoveled up by a spoiler below and behind the grille and enters the bodywork through two slots you can’t even see unless you lie down in front of the car.

There is an answer for every question and a reason for every one of the Corvette’s characteristics. Duntov will talk of the battles and compromises that have been thrashed out between him and the stylists, product planners, and memo writers but he is adamant about one feature — throughout production he has stood firmly against those who would have reduced the Corvette’s stability at high speed.

View Photos

View Photos

Leave a Reply