|

|

Back before we knew how to drive, we used to invite professional racers to help us evaluate challenging machinery. One of these was stock-car driver Bobby Allison. In our February 1974 issue, we put Allison and his nonexistent brain-to-mouth filter into a 1974 Porsche 911. “To be fair,” Allison said, “the car has unique characteristics, and some people may like it. I don’t. I think they are $12,000 imported Corvairs.”

Even all these years later, we can still see the jaws of Porschephiles dropping as they read his opinions of a car that many would have swapped their first-borns for.

Allison bashed the 911 for its notorious tendency to swap ends. Comparing three new 1974 Porsches—a 911, a Targa, and a Carrera—he complained that “when you’d go too deep into a corner and lift, the car would begin to spin. And if you went ahead and did the natural thing—lifted, or put on the brakes—then the car would spin.”

This longstanding hairy nature of the Porsche 911 is almost as legendary as its prodigious performance. The 911 and oversteer are so intertwined; any car nut born during or after the Nixon years was weaned on stories that warned it was a sports car suited only for skilled hands, and anyone else was risking his or her life by driving one fast. One might have wondered, “If the 911 is so treacherous, why is it also so coveted?”

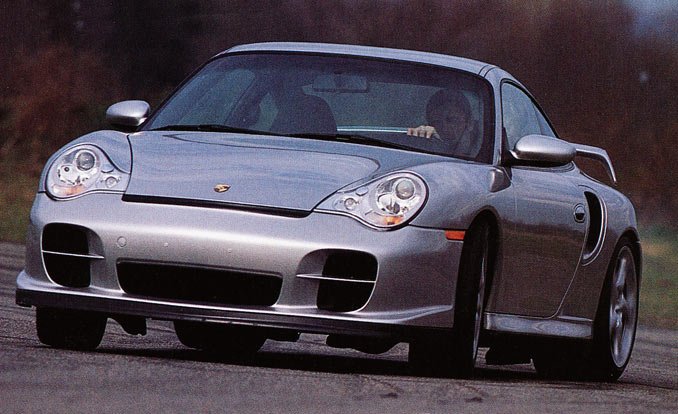

A spin in any modern 911 will make you wonder about these warnings. Getting a current 911 to swing its tail is about as easy as convincing the Cseremeister to spring for a holiday party. And if you do somehow manage to get the car loose, the stability-management system will catch you. In achieving this modern-day stability, has Porsche lost a big chunk of its hellbent character? Has the 54-year-old sports-car company that’s about to introduce a sport-ute grown a spare tire around its middle?

A car that would certainly qualify as one of the rowdy and twitchy Porsches is the 1973 Carrera “RS” (for rennsport). The RS was the lightest, fastest, and most expensive roadgoing 911, and its primary purpose was to bring the 911 racing success.

In 1973, as today, car companies that wanted to go racing could build expensive one-off exotic machines to vie for the overall win at races such as Le Mans and the 24 Hours of Daytona. They could also race in a lesser class, known then as the GT class in the U.S. and the GTS class at Le Mans, with production-based cars such as the 911.

But to enter a car in the GT class, an automaker had to build at least 500 road-legal cars. In 1972, before the 911 Carrera RS, the swiftest Porsche was the 911 S, of which 5094 were sold that year. But Porsche feared Ferrari’s GT car, the 365GTB/4 Daytona, would trounce it, so a new, faster—but still salable—911 was ordered up.

Work began on this ultimate 911, the Carrera RS, in early 1972. Porsche lightened the car, increased the cylinder bore of the flat-six to bump displacement from 2.4 liters to 2.7, and gained 20 horsepower for a total of 207 at 6300 rpm. The steel body, usually 0.04 to 0.05 inch thick, was replaced with panels that measured less than 0.03 inch. The interior was stripped of its carpets, radio, sound-deadening materials, even the passenger-side sun visor. The use of Bilstein shock absorbers saved 7.7 pounds. Seven-inch-wide rear rims replaced the six-inchers, and to fit them under the bodywork, the rear fenders were flared.

Other bodywork included a fiberglass decklid with a “bürzel” or ducktail to reduce rear lift and drag. Up front, a chin spoiler and an oil cooler were added. The resulting car weighed about 300 pounds less than the 2500-pound 1973 911 S, and since the new engine was not approved for sale in the U.S., Porsche had to sell the car without the aid of its largest market. Only about $500 was added to the top-of-the-line 1973 911’s price of $9800.

In the months before the car’s official debut at the Paris auto show in October 1972, Porsche brass were worried about having to sell 500 stripped 911s at a higher price. Personnel entitled to company cars were put in RSs. A big ad campaign ensued, and dealers were pounded to push the new car. Within a week of the RS’s introduction, all 500 cars were spoken for. Porsche quickly put another 500 into production and tacked on a $300 premium. Those sold, too, and Porsche didn’t turn off the RS faucet until late in August 1973, after 1800 RSs in all were sold.

Leave a Reply