Originally published in Sports Cars Illustrated in March 1961.

PROBLEMATIC BRAKING

No Sting Ray problem has been more persistent than the brakes. As you’ll recall, the SS was equipped with an unique Kelsey-Hayes double-booster system designed to prevent rear brake lockup under high deceleration, using a mercury switch in an involved arrangement of wires and piping described completely in our SS story. One of the ’57 problems was too-small line diameters that caused a delay in the system’s response; this was rectified then but there still seemed to be a slight lag in the Sting Ray’s reaction times, leading to uncontrollable brake lockup — usually at highly critical moments.

At first this lockup was attributed to the combination of the often-erratic cerametallic linings with the Chrysler Center-Plane brake mechanisms that were and are being used, these mechanisms being the two-leading-shoe type which is prone to locking if linings aren’t just right. First step, then, was to start using the Moraine sintered-iron linings now fitted to competition Corvettes. Tried first at Lime Rock in July of ’59, these linings are used with stock cast iron Corvette drums that are given a fine surface finish and closely matched to the individual linings. At first the sintered linings were riveted in place, then after Bridgehampton in 1960 they were welded to the shoes. During this period the Delco-Moraine Division has experimented with many different sintered iron lining compositions on the Sting Ray, contributing ultimately to the consistency of the Corvette’s linings today.

This wasn’t the whole answer, though, and the Kelsey-Hayes system was finally thrown out after the Road America 500 in 1959 and replaced by a single Hydrovac booster, modified by Bendix to allow changes in pedal pressure to be made. The brakes are still not very impressive, which leads to a logical question: why not discs? This falls in the category of the ball joints for the rear suspension; it would be nice but it’s a very big job, involving extensive changes in the hub layout to keep the discs from causing an excessively high kingpin offset. The Sting Ray’s weight is naturally a factor here. With the old body and original brake system, the car weighed 2154 pounds dry, leading to an estimate of a present dry weight of 2000 pounds. Wet, with the 31-gallon normal fuel tank full, it should weigh about 2360 pounds. It’s no Birdcage, but neither is it disgracefully heavy.

MODEST POWERPLANT

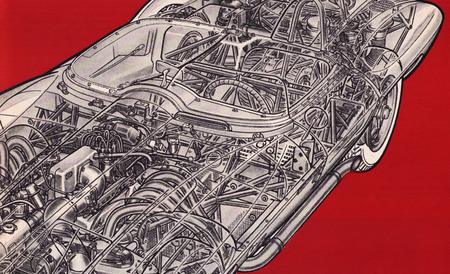

The Sting Ray’s excellent performance in its class (C Modified) is surprising in view of its “cooking” engine, as Stirling Moss described the SS unit at Sebring. In fact the Sting Ray crew doesn’t even claim as much power for it as the latest hot production Corvettes are boasting! They say 300 genuine horses, as installed, with 280 bhp at the clutch, at about 6200 rpm. Usual rev limit is 6500 rpm, with 6800 okay in top gear. Torque comes to a peak at 44-4500 rpm. This is done with a stock-sized Chev 283 engine, on an 11 to one compression ratio. Dean Bedford and Mitchell have resisted the temptation to “go Scarab” on displacement, feeling that the Chev only becomes less reliable in the process and more demanding of maintenance.

At Sebring the Corvette SS used the prototype aluminum cylinder heads, without valve seat inserts. These heads have been used on the Sting Ray, as have aluminum heads with inserts. Both work with equal high efficiency and reliability on this carefully-maintained car. Between the heads a 1957 Rochester fuel injector continues to supply fuel-air mix, set a shade on the rich side to keep the engine running cool. The normal racing fuel consumption is about 6 miles per gallon; a supplementary tank that brings the capacity to 45 gallons is used for the Road America 500.

Leave a Reply