At any rate, the bugs aren’t yet out of Porsche’s vented discs. True, they run cooler, making them less prone to fade, and lengthening pad life, but they are more difficult to modulate. If Ford’s experience with vented discs on their Le Mans-winning Mk. II is any indication, the problem may be that the discs aren’t dimensionally and/or geometrically stable. In our 80-0 mph braking test, the left rear wheel would invariably lock up, and the shortest stopping distance we could record was 271 ft. (.71G). Not half bad, but we knew the car could do better. Later, we sampled another 911S, and, after heating up the rather hard pads, it stopped from 80 mph in 242 ft. (.88G), but we have stopped a solid-disc 911 in 218 ft. (.98G), which is more like what the true potential is.

Normally, we measure a car’s cornering power by clocking lap times on a skid pad of a known radius. We don’t use an accelerometer, or Tapley meter, because it adds the vehicle’s roll angle to the absolute lateral acceleration, and there is no accurate way to distinguish between the two. (Similarly, on braking and acceleration, the vehicle’s pitch angle is automatically included in the reading.) However, during one phase of this test, we had the opportunity to ride shotgun with expert Porsche pilot Lake Underwood as he booted the 911S around a road circuit. Out of curiosity, we installed a lateral accelerometer to measure the 911S’s cornering power. On level, unbanked turns, the instrument showed a maximum reading of .93G on right-hand corners, and .89G on left-hand bends. Subtracting a generous 9° (.10G) for roll angle, the 911S’s limit of controllability is well over .81G.

|

|

The 911S’s oversteer characteristic appears early in the car’s cornering range. At low lateral accelerations, it understeers mildly. From .40G on up, less and less steering lock is needed to keep this car on a given course. By .70G, it’s in a full-blooded four-wheel drift, and the steering behavior is back-tracking toward neutral-steer. Beyond the limit of the tires’ rolling adhesion, the 911S reacts like any car with a rearward weight bias, and spins, or, if you’re quick enough to catch it, power-slides like an old dirt-track roadster. All told, Porsche’s admonition, “not for the novice” is a bit gratuitous. Within normal driving limits and with reasonable caution, the 911S handles predictably, controllably, and head and shoulders above practically anything else on the road.

There’s always room for improvement, however, and the present limitations on the 911S’s absolute cornering power are imposed by its wheels and tires. We were stunned to learn that the rim width of those flashy new wheels is still only 4-1/2 inches, a mere half-inch wider than a Volkswagen’s, and unchanged since Porsche went from 16-in. to 15-in. wheels in the dim dawn of time. Four-and-a-half inches was unfashionably skinny even then, and is almost inconceivable today. Porsche ballyhoos the notion that their racing program improves the breed of their production cars, but the competition-bred lesson of the benefits of wide-rim wheels has apparently gone unheeded. One-inch wider rims alone would have wrought as much improvement in the car’s handling ability as all their tricks with rear anti-sway bars, stiffer shocks and spring rates, and radial-ply tires. Wide-rim racing wheels are available from Porsche for competition drivers, and American Racing Equipment in San Francisco is doing a land-office business in 5- and 6-in. mag wheels for disc-braked Porsches. The introduction of Porsche’s own mag wheel would have been an ideal opportunity to cash in on the trend, but Stuttgart fumbled the ball. We can only surmise that steps will soon be taken to correct this state of affairs. In the meantime, it is of some consolation that the new wheels aid brake heat dissipation and reduce unsprung weight.

The 911S’s radial-ply tires, German Dunlop SPs, are the other limiting factor. Radial-ply tires are generally advantageous, developing a higher cornering force at a lower slip angle than conventional tires. They do this by keeping more rubber on the road through a softer lateral compliance—the tread stays flat on the ground while the sidewall rolls. This gives radials an odd feel; they mush sideways until the slack is taken up, then they grip. The SPs, in particular, have an odd tread pattern, like a knobby snow tire, with S-shaped cleats and a deep (1/4-inch) tread depth. The cleats are so tall that they bend like willows under side loads. Coupled with the normal mushiness of radials, the SPs give a sensation somewhat akin to riding on bristles. It would be interesting to try a 911S with a shallow-tread radial-ply tire, like the Michelin X, or an American high-performance tire, like the Firestone Wide Oval.

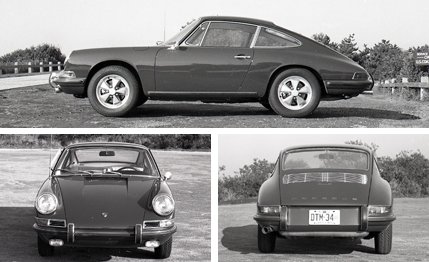

View Photos

View Photos

Leave a Reply